Should We Reject Animal Source Foods To Save The Planet?

A clutch of fishing villages dot the coast about Kilifi, north of Mombasa in Kenya. The waters are home to parrot fish, octopus and other edible species. But despite living on the shores, the children in the villages rarely consume seafood. Their staple meal is ugali, maize (corn) flour mixed with water, and most of their nutrition comes from plants. Well-nigh half the kids here have stunted growth — twice the national rate.

In 2020, Lora Iannotti, a public-health researcher at Washington University in St. Louis, and her Kenyan colleagues asked people in the villages why the children weren't eating seafood, even though all the parents fish for a living; studies show that fish and other animal-source foods can improve growth1. The parents said it made more financial sense for them to sell their catch than to consume it.

So, Iannotti and her team are running a controlled experiment. They have given fishers modified traps that have minor openings that allow young fish to escape. This should improve spawning and the health of the overfished ocean and reef areas over time, and eventually increase incomes, Iannotti says. And then, for half the families, community health workers are using home visits, cooking demonstrations and messaging to encourage parents to feed their children more than fish, especially plentiful and fast-growing local species such as 'tafi', or white spotted rabbitfish (Siganus canaliculatus) and octopus. The scientists will runway whether children from these families eat better and are growing taller than ones who don't receive the messaging.

The aim of the experiment, says Iannotti, is to understand "which sea foods can we choose that are healthy for the ecosystem besides as healthy in the diet". The proposed diet should also exist culturally acceptable and affordable, she says.

Iannotti is wrestling with questions that are a major focus of researchers, the United nations, international funders and many nations looking for diets that are good for both people and the planet. More than 2 billion people are overweight or obese, mostly in the Western world. At the same time, 811 million people are not getting enough calories or nutrition, mostly in low- and middle-income nations. Unhealthy diets contributed to more than deaths globally in 2017 than whatsoever other factor, including smokingii. As the world's population continues to rise and more people kickoff to eat like Westerners do, the production of meat, dairy and eggs volition need to rise by nearly 44% by 2050, according to the UN Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO).

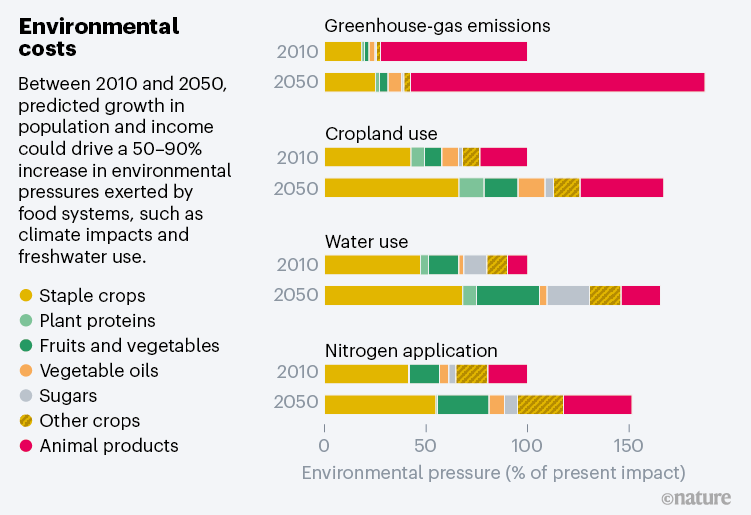

That poses an environmental problem alongside the health concerns. Our current industrialized nutrient system already emits about one-quarter of the globe's greenhouse-gas emissions. It also accounts for 70% of freshwater use and 40% of state coverage, and relies on fertilizers that disrupt the cycling of nitrogen and phosphorus and are responsible for much of the pollution in rivers and coasts3.

In 2019, a consortium of 37 nutritionists, ecologists and other experts from 16 countries— the EAT–Lancet Committee on Nutrient, Planet, Health — released a report4 that called for a wide dietary change that would take into account both diet and the environment. A person following the EAT–Lancet reference diet would exist 'flexitarian', eating plants on most days and occasionally a modest amount of meat or fish.

The report provoked a flurry of attending towards sustainable diets, and some criticism about whether information technology was practical for everyone. Some scientists are at present trying to test environmentally sustainable diets in local contexts, without compromising diet or dissentious livelihoods.

"We need to make progress toward eating diets that have dramatically lower ecological footprints, or information technology'll exist a affair of a few decades before we start to run into global collapses of biodiversity, land use and all of it," says Sam Myers, managing director of the Planetary Health Brotherhood, a global consortium in Boston, Massachusetts, that studies the health impacts of environmental change.

Emissions on the menu

Producing food generates so much greenhouse-gas pollution5 that at the current rate, even if nations cutting all non-food emissions to zilch, they still wouldn't be able to limit temperature ascent to i.5 °C — the climate target in the Paris agreement. A large proportion of emissions from the nutrient system — 30–l%, co-ordinate to some estimates — comes from the livestock supply chain, because animals are inefficient at converting feed to food.

In 2014, David Tilman, an ecologist at the University of Minnesota in Saint Paul, and Michael Clark, a food-systems scientist at the University of Oxford, UK, estimated that changes in urbanization and population growth globally between 2010 and 2050 would cause an 80% increase in food-related emissionshalf-dozen.

Just if everyone, on average, ate a more found-based diet, and emissions from all other sectors were halted, the earth would have a 50% chance of meeting the 1.v °C climate-modify targetfive. And if diets improved alongside broader changes in the food system, such as cutting downwardly waste matter, the take chances of hitting the target would ascent to 67%.

Such findings are not pop with the meat industry. For example, when in 2015, the US Section of Agronomics was revising its dietary guidelines, which happens every v years, it briefly considered factoring in the surround after researchers lobbied the advisory committee. But the thought was overruled, allegedly in response to industry pressure, says Timothy Griffin, a food-systems scientist at Tufts University in Boston, who was involved in the lobbying effortvii. Nonetheless, people took notice of the attempt. "The biggest accomplishment is information technology brought a lot of attention to the issue of sustainability," he says.

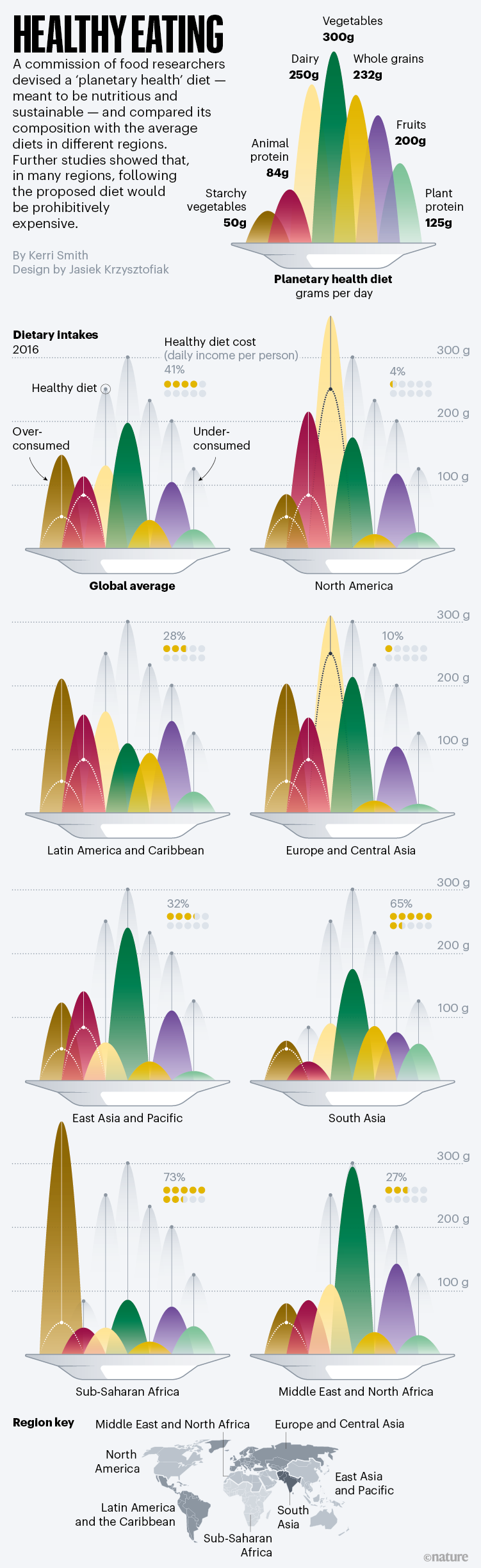

The Consume–Lancet Commission, which was funded by Wellcome, a Great britain-based clemency, helped to build a stronger example. Nutritionists reviewed the literature to craft a basic healthy diet composed of whole foods. Then the team set environmental limits for the diet, including carbon emissions, biodiversity loss and the use of fresh water, country, nitrogen and phosphorus. Breaching such environmental limits could brand the planet inhospitable to humansviii.

They concluded up with a diverse and mainly plant-based meal plan (come across 'Healthy eating'). The maximum crimson meat the 2,500-calorie per twenty-four hour period diet allows in a week for an average-weight xxx-year-old is 100 grams, or one serving of red meat. That'due south less than one-quarter of what a typical American consumes. Ultra-processed foods, such as soft drinks, frozen dinners and reconstituted meats, sugars and fats are mostly avoided.

This diet would salve the lives of about 11 million people every year, the commission estimated4. "It is possible to feed 10 billion people healthily, without destroying ecosystems further," says Tim Lang, nutrient-policy researcher at the Urban center Academy of London and a co-author of the Consume–Lancet written report. "Whether the hardliners of the cattle and dairy industry like it or not, they are really on the back foot. Change is at present inevitable."

Many scientists say the Swallow–Lancet diet is excellent for wealthy nations, where the average person eats 2.6 times more meat than their counterpart in depression-income countries, and whose eating habits are unsustainable. Merely others question whether the diet is nutritious enough for those in lower-resource settings. Ty Beal, a scientist based in Washington DC with the Global Brotherhood for Improved Nutrition, has analysed the diet in unpublished calculations and found that it provides 78% of the recommended zinc intake and 86% of calcium for those over 25 years old, and simply 55% of the atomic number 26 requirement for women of reproductive age.

Despite these critiques, the nutrition has put environmental concerns front and centre."Until EAT–Lancet, I don't think it had been at the top of policymakers' minds that sustainability should be integrated into this global conversation nearly dietary alter," says Anne Elise Stratton, a food-systems scientist at the Academy of Michigan in Ann Arbor.

The diet is not a ane-size-fits-all recommendation, stresses Marco Springmann, a food scientist at the University of Oxford who was part of the EAT–Lancet core modelling team.

Since the report was published, public-health scientists around the globe have been studying how to make the diet realistic for people the world over, whether an overweight adult or an under-nourished child.

Rich diets

Nutrition researchers know that most consumers do not follow dietary guidelines. So some scientists are exploring ways to convince people to adopt healthy, sustainable diets. In Sweden, Patricia Eustachio Colombo, a diet scientist at the Karolinska Institute in Stockholm, and her colleagues are quietly testing a sustainable diet in schools. Their work piggybacks on a social movement that began in Scandinavian countries chosen the New Nordic Diet, which promotes consumption of traditional, sustainable foods such as seasonal vegetables and free-range meat.

Eustachio Colombo and her colleagues used a calculator algorithm to analyse existing school lunches at a primary school with almost 2,000 students. The algorithm suggested means to make them more nutritious and climate-friendly, such as reducing the corporeality of meat in a typical stew and adding more beans and vegetables. The children and parents were informed that lunches were existence improved, but did not know details, Eustachio Colombo says. Most kids did not detect, and in that location was no more food waste than before9. The same experiment is now being re-run in 2,800 children.

"School meals are a near unique opportunity to foster sustainable dietary habits. The dietary habits we develop every bit children, nosotros tend to stick to them into adulthood," Eustachio Colombo says.

The diet is very different from the Consume–Lancet i, she says. Information technology is cheaper and includes more starchy foods such as potatoes, which are a staple of Swedish cuisine. It is too more than nutritious and culturally adequate, she says. "This highlights the importance of tailoring the Eat-Lancet diet to the local circumstances in each land or even within countries," she says.

Across the Atlantic, some academics and restaurateurs are trialling the diet in low-income settings. In Baltimore, Maryland, a collaboration between a catering business organisation and a eatery, both forced to close during the COVID-nineteen pandemic, started taking donations and providing gratis meals based on the Consume-Lancet diet to families who live in 'food deserts' — areas where at that place is little access to affordable, nutritious food. One meal had salmon cakes with mixed seasonal vegetables, Israeli couscous and flossy pesto sauce.

Researchers at the Johns Hopkins Academy School of Medicine in Baltimore surveyed 500 people who tried the meals and institute that 93% of the 242 people who completed the survey said they either loved or liked it10. The downside? Each donation-funded repast price United states of america$10 — five times the corporeality currently provided by the US food-stamp programme.

"Information technology's very clear that if you accept a huge shift in diets, y'all could swing the surround impact for the better, but in that location's cultural barriers and economical barriers to that," says Griffin.

Hard to breadbasket

For researchers exploring hereafter diets in some low- or middle-income nations, one hurdle is finding out what people are eating in the first place. "Information technology's literally like a black box to me correct at present," says Purnima Menon at the International Food Policy Inquiry Institute in Delhi, who has been studying diets in India. The information on what people are eating are a decade old, she says.

Getting that information is crucial, considering India ranks 101 out of 116 countries in the Global Hunger Index and has the greatest number of children who are likewise thin for their height.

Using what'south available, Abhishek Chaudhary, a food-systems scientist at the Indian Establish of Technology Kanpur, who was part of the Swallow–Lancet team, and his colleague Vaibhav Krishna at the Swiss Federal Institute of Technology in Zurich used a computer program and local environmental data on water, emissions, land utilize and phosphorus and nitrogen use to design diets for all of India'due south states. The algorithm suggested diets that would run across nutritional requirements, cutting food-related emissions past 35% and wouldn't stress other ecology resources. But to abound the required corporeality of food would require 35% more land — which is impractical in the overcrowded nation — or higher yields. And food costs would be 50% higher11.

Healthy, sustainable diets are expensive elsewhere, too. The dietary diversity brash by EAT–Lancet — nuts, fish, eggs, dairy and more — is incommunicable to access for millions of people, says Iannotti.

In fact, for the average person to eat the diet in 2011 — the well-nigh recent data set bachelor on nutrient prices — would have toll a global average of $2.84 per twenty-four hour period, most 1.6 times higher on average than the cost of a bones nutritious meal12.

There are other impracticalities. Have restrictions on meat, for instance. In places with nutrient deficiencies and where the diet'due south prescribed foods are not bachelor, animal-source products are a crucial source of easily bioavailable nutrients in add-on to plants, Iannotti says. In many places in depression-income nations, farming systems are pocket-size-calibration and include both crops and domesticated animals, which can be sold in times of family need, says Jimmy Smith, manager-general of the International Livestock Inquiry Institute in Nairobi.

"The farmer in the highlands of Ethiopia doing dairy has three or iv animals in his or her lawn, and each of these animals is a member of the family, they have names," he says.

Menon says that for now, scientists in low- and heart-income regions are more concerned about delivering nutrition than preserving the environment. The FAO has organized a commission to do a much more than comprehensive analysis than EAT–Lancet'southward. The new analysis will be more globally inclusive and include topics such as food security and sustainability of the livestock sector, says Iannotti, who is part of the committee. It will exist published in 2024. "They don't feel every bit if it was entirely balanced or holistic in its review of the evidence," she says. "Permit's go further and make certain we have evidence from around the world."

The way to detect sustainable diets in poor nations is past working closely with communities and farmers, every bit in Kilifi, scientists say. Clark, having mapped out diet at a global scale using model-based projections, thinks that food-system scientists now need to find the local adjustments and fixes to get people to eat ameliorate.

"People working in food sustainability need to go into communities and ask, 'hey, what'due south salubrious?'" he says. "And then, given that baseline, how can we start working towards outcomes that those communities are interested in."

Source: https://www.nature.com/articles/d41586-021-03565-5

Posted by: chisolmgrephersur.blogspot.com

0 Response to "Should We Reject Animal Source Foods To Save The Planet?"

Post a Comment